ARM Provides World’s First Multi-Site Long-Term Data Record of Ice-Nucleating Particles

Published: 21 June 2024

Editor’s note: Jessie Creamean, a research scientist at Colorado State University and an ARM mentor for ice-nucleating particle collection and analysis, sent in the following update.

Come one, come all! A first for the burgeoning global ice nucleation community and beyond. Do you like clouds? Are you a fan of ice? Then read on, dear frosty friends, for those persnickety little ice-nucleating particles (INPs) are making orographic waves in clouds and the ARM data world.

But why care about those tiny, rare, enigmatic INPs? Well, my wondrous readers, INPs are the little key pieces to the 1,000,000-piece cloud puzzle. Perhaps they are that puzzle piece that fell on the floor and your dog accidentally chewed. Yes, they are that hard to find. But they are crucial to finishing that puzzle you have been working on oh so hard.

Now, back to the real world. Without INPs, clouds would not have their characteristic mixed- or ice-phase idiosyncrasies that make them important for steering the world’s energy budget, all that lovely rain we wish for in the spring to make our gardens grow, and those feet of snow we wish for so we can have a rad powder day on the slopes.

But I digress. Your trusty DOE ARM INP mentor team, including myself (lead mentor Jessie Creamean), co-lead mentor Tom Hill, and associate mentors Carson Hume and Tim Devadoss, have been hard at work to give you the cool data set of your cloudy dreams. Our workhorse, the ice nucleation spectrometer (INS), is the gift that keeps on giving those INP data. We have now released all INP data up to date at sites spanning from sea level up to the peaks of the Colorado Rockies. Heck, we even have our hands in the truly chilling scape of the Arctic.

We’re talking massive amounts of INP data, from the warm, sunny California beach during the Eastern Pacific Cloud Aerosol Precipitation Experiment (EPCAPE) to the stormy Texas heat of the TRacking Aerosol Convection interactions ExpeRiment (TRACER) to the snow-capped Colorado Rockies—John Denver’s favorite mountain range—during the Surface Atmosphere Integrated Field Laboratory (SAIL) campaign, and up to the polar bear haven of the third ARM Mobile Facility (AMF3) at Oliktok Point, Alaska (OLI).

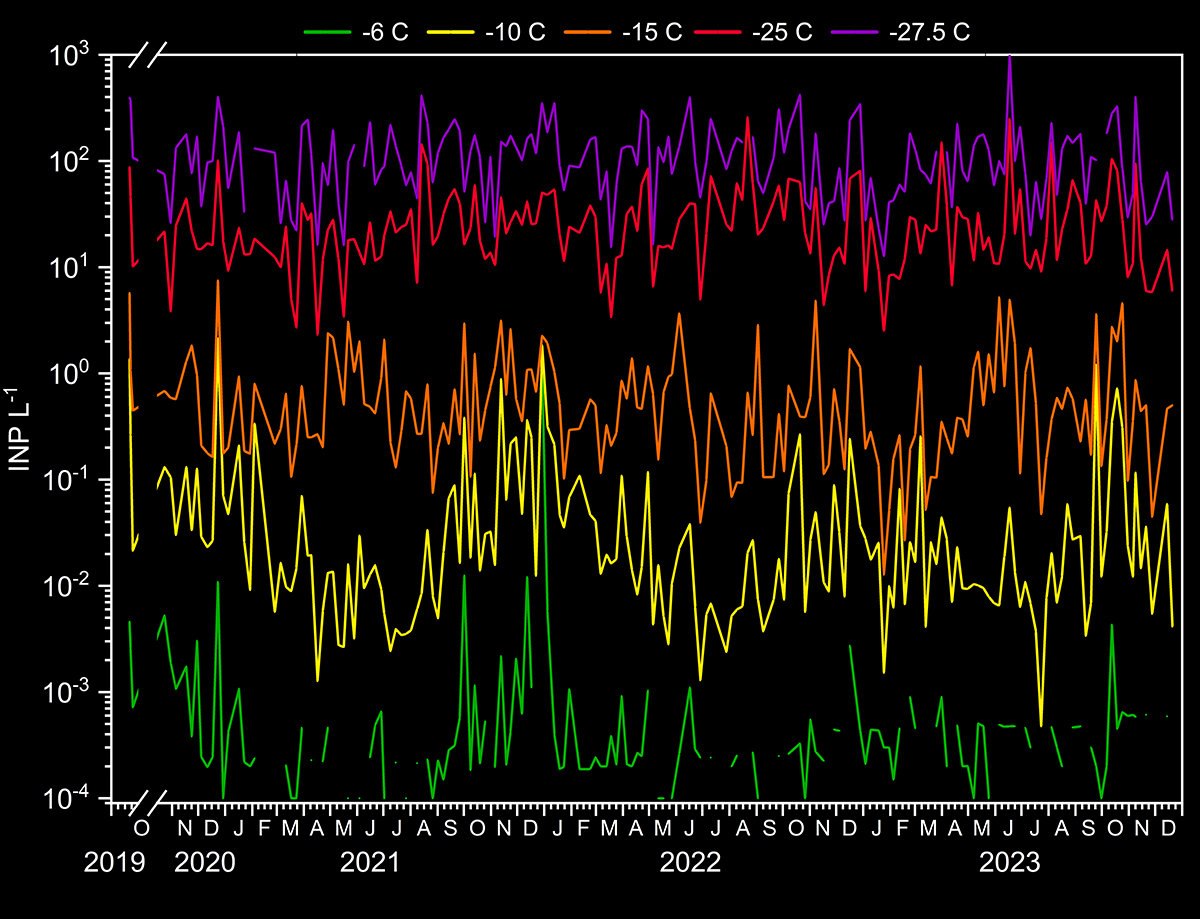

But who could forget our “rock,” the trusty land of corn and grain at the Southern Great Plains (SGP) atmospheric observatory in Oklahoma? From the SGP, we now have over a whopping three years’ worth of INP data. That’s right, folks, you heard it correctly, over three years! Modelers, please refrain from drooling. We know those long-term INP records are your ultimate desire for closure studies to test the robustness of your beloved INP parameterizations.

The chilling tale doesn’t end here. Your icy INP mentors just started filters hoovering up those INPs in the air Down Under for the Cloud And Precipitation Experiment at kennaook (CAPE-k). We hope to have the first results from CAPE-k by the end of the year. And who could forget the Bankhead National Forest (BNF)? Stay tuned in fall 2024 for INPs living in the fantastic forests of the Southeastern United States. We also have the “courage” to measure INPs at not one but two sites during the Coast-Urban-Rural Atmospheric Gradient Experiment (CoURAGE) to compare the elusive urban INPs to their rural counterparts, starting in December 2024. And let’s face it, we miss our polar bear friends in the Arctic, so back we will go to establish baseline INP measurements at the North Slope of Alaska (NSA) observatory in summer 2025.

I must warn you of another John Denver reference. After all, I live in Colorado, and the man is a folk music wonder with the voice of an angel. While INPs won’t be “leaving on a jet plane,” they do know when they’ll be back again—on the DOE ARM tethered balloon system (TBS), that is. That’s right. Our little first-class TBS passenger, the IcePuck INP filter sampler, has flown through the skies during the Agricultural Ice Nuclei at SGP (AGINSGP) and SAIL Aerosol Vertical Profiles (SAIL-AVP) deployments. Future TBS measurements are possible, at the request of all you wonderful future principal investigators out there.

To sum things up, the world’s first multi-site long-term INP data record is now publicly available through ARM, and it’s cooler than a penguin sipping a slushie in a blizzard. But we’re not stopping there. With campaigns popping up in Australia and the Southeastern United States, and more Arctic adventures on the horizon, we’re on a mission to unlock the mysteries of those devious little INPs across the globe. So grab your winter gear, folks, because these data are about to make it rain … or snow … or maybe even sleet.

Until next time, my frosty friends!

Want to Use the INP Data?

Currently, INP concentration data are available from the land-based INP samplers at EPCAPE, SAIL, TRACER, OLI, and the SGP, and the TBS IcePuck deployments at SAIL and the SGP. Access these data from the ARM Data Center. (To download the data, first create an ARM account.)

Check back with the ARM Data Center for data availability from current and future sites.

For more information about the INS, see the instrument web page and instrument handbook. Information on the IcePuck can also be found in the INS instrument handbook.

Please contact Creamean and Hill with questions or comments about the data.

To cite the land-based INP data, please use doi:10.5439/1770816. To cite the TBS data, please use doi:10.5439/2001041.

Keep up with the Atmospheric Observer

Updates on ARM news, events, and opportunities delivered to your inbox

ARM User Profile

ARM welcomes users from all institutions and nations. A free ARM user account is needed to access ARM data.