Unexpected Riches Come From a Change in Plans

Published: 17 May 2021

Globe-trotting instrument’s extended stay at ARM’s Eastern North Atlantic observatory results in a bounty of data

Editor’s note: This is the third article in a series looking at how ARM has continued to support atmospheric science during the pandemic.

When Naruki Hiranuma prepared to send his refrigerator-sized research instrument from the United States to the Azores in early 2020, he did not plan on it being there almost a year longer than scheduled. But the prolonged stay during the COVID-19 pandemic turned out to be a boon for Hiranuma’s studies on ice-nucleating particles (INPs).

Such particles come from sources such as soot, airborne microbes, plant-derived materials, dust, and sea spray. INPs play an important role in cloud and precipitation formation and suppression, says Hiranuma. However, researchers do not really know what makes for a good INP or how many INPs are in the atmosphere.

“INPs are the special population of aerosol particles,” says Hiranuma, an assistant professor of environmental science at West Texas A&M University in Canyon, Texas.

Hiranuma is working on a five-year INP project funded by his U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Early Career Research Program award, which he won in 2018. Hiranuma’s project relies on data from the Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) user facility’s three fixed-location atmospheric observatories.

In late 2019, Hiranuma was onsite for two INP field campaigns at ARM’s Southern Great Plains (SGP) atmospheric observatory in Oklahoma. He was a co-investigator for one campaign led by Daniel Knopf, a professor at Stony Brook University in New York. Hiranuma led the other campaign, Examining the Ice-Nucleating Particles from SGP (ExINP-SGP). Both campaigns used his Portable Ice Nucleation Experiment (PINE) instrument, a novel type of cloud simulation chamber.

PINE ran for 45 consecutive days, providing what Hiranuma says were the first automated and continuous measurements of ambient INP concentrations. The 400-pound, temperature-controlled chamber measures INPs about every 10 minutes and can run remotely.

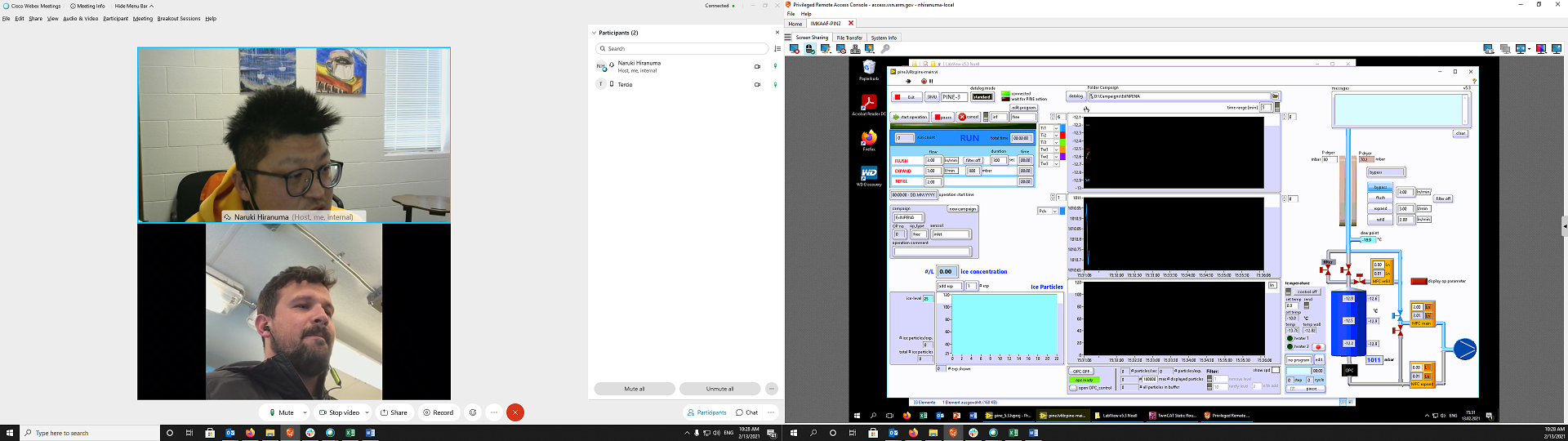

In February 2020, an ARM team from Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico shipped PINE to ARM’s Eastern North Atlantic (ENA) atmospheric observatory in the Azores. Hiranuma’s team would control the instrument on Graciosa Island from West Texas.

PINE was to run at the ENA for 45 days, from May to June 2020, before going to Alaska for a multiyear ARM campaign—but that plan soon changed because of the pandemic.

Teamwork in Action

Although PINE reached the ENA on time for its scheduled start date, Hiranuma could not travel to oversee the installation, so the campaign was delayed.

After several months, with COVID travel restrictions still in place, Hiranuma spoke with the ARM team about what to do next. Travel within Europe was more open, so Hiranuma asked one of his German collaborators, Larissa Lacher, if she could go to the Azores. Lacher is from the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, which led the development of PINE.

Upon testing negative for COVID, Lacher traveled to the ENA and helped the site technicians set up PINE, including the aerosol stack that feeds into the chamber.

The ENA PINE campaign began in late September, but ARM extended it beyond 45 days. Staff in Alaska would not be able to install the instrument during the winter, and the planned PINE host site in Utqiaġvik (formerly Barrow) was under construction. That site—the NOAA Barrow Atmospheric Baseline Observatory—is next door to ARM’s North Slope of Alaska atmospheric observatory.

Throughout the campaign, Hiranuma worked virtually with ENA technicians Carlos Sousa, Bruno Cunha, and Tercio Silva to check on data and fix minor issues.

“It’s mostly because of his diligence and cooperating with our technicians and giving them very detailed guidance,” says ENA Operations Manager Hannah Ransom, who is at Los Alamos. “And I think we’ve all gotten better at things like teleconferences and Skype and Microsoft Teams.”

Hiranuma and the ARM team agree that their online collaboration helped make the PINE campaign a success. The campaign ended in April, giving Hiranuma’s team about 200 days of data—five months more than originally planned.

Data Discoveries

The wealth of ENA data is already paying off. Hiranuma says that his team saw a strong correlation between INPs and cloud-forming particles called cloud condensation nuclei (CCN).

“I think no one has seen the correlation between INP (ice-nucleating particles) and CCN (cloud condensation nuclei), and with this marine-dominant station, I think we found it for the first time.”

Naruki Hiranuma, West Texas A&M University

“I think no one has seen the correlation between INP and CCN, and with this marine-dominant station, I think we found it for the first time,” says Hiranuma.

The April 2021 European Geosciences Union (EGU) General Assembly included a presentation of early findings from the ENA PINE campaign.

The presenter, Elise Wilbourn, who works with Hiranuma at West Texas A&M, noted higher INP concentrations in the fall than in the winter. Wilbourn says that Graciosa Island has higher local marine biological productivity in the winter, so there are probably some INP sources from slightly farther away. “But,” she adds, “we do see mostly marine INPs at this site over the whole time period.”

After getting 6.5 months of ENA data, Hiranuma’s team is excited for the even longer data set expected from Alaska. PINE is scheduled to start up in Utqiaġvik this summer, and ARM has approved the campaign to run for three years. As with the other PINE campaigns, ARM instruments will provide additional measurements.

“I think that investigating INPs across the world, especially in the Arctic, will be very, very important to understand the projections of the global climate in the future,” says Hiranuma.

Currently, Hiranuma and Wilbourn plan to travel to Utqiaġvik to help with the installation. If they cannot travel, they will work virtually with the onsite technicians. The technicians will also have documentation from ENA technicians, including photos and video, on how to set up and take down the instrument.

‘The Game-Changing Project’

In April, Hiranuma actually finished two ARM campaigns—the one at the ENA and another at the SGP (ExINP-SGP II).

Starting in November 2020, SGP staff collected ambient dust every few days from a particle sampler placed on the rooftop of an Aerosol Observing System trailer. Practicing social distancing and wearing masks, Wilbourn and West Texas A&M graduate student Kimberly Sauceda visited the SGP in November to set up samplers and collect soil from the site.

Soil and dust collected during ExINP-SGP II will be used in a summer 2021 INP experiment in Germany. The experiment will take place in the cloud chamber that inspired the much smaller PINE’s construction. The German chamber is 84 cubic meters, whereas PINE has a volume of 10 liters.

Hiranuma has already written about data from the first ExINP-SGP campaign. He co-authored a PINE overview paper published in February 2021 by the journal Atmospheric Measurement Techniques.

Hiranuma also co-wrote a March 2021 paper in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics that cites pre-PINE INP research from the SGP. The paper looks at INPs in precipitation samples from the Texas Panhandle.

It is possible that PINE could return to the SGP after its time in Alaska. Hiranuma and his collaborators are interested in proposing a multi-season SGP PINE campaign.

Hiranuma’s original plan remains: Feed INP data from the ARM fieldwork and laboratory studies into earth system models. With modelers and experimentalists working together using DOE facilities and resources, says Hiranuma, “I think this can be the game-changing project.”

See all articles in the “Science Still Going, ARM Data Still Flowing” series.

Keep up with the Atmospheric Observer

Updates on ARM news, events, and opportunities delivered to your inbox

ARM User Profile

ARM welcomes users from all institutions and nations. A free ARM user account is needed to access ARM data.